|

|

(Alessandro Dahan/Getty Images)

|

Full Story: Nature (10/4)

- NEWS

Believe it or not, this lush landscape is Antarctica

Hummocks of moss cover Ardley Island off the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula.Credit: Dan Charman

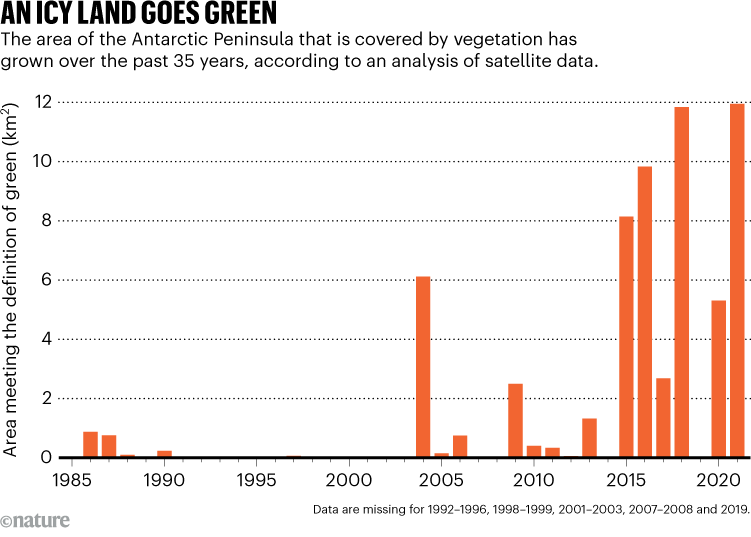

A fast-warming region of Antarctica is getting greener with shocking speed. Satellite imagery of the region reveals that the area covered by plants increased by almost 14 times over 35 years — a trend that will spur rapid change of Antarctic ecosystems.

“It’s the beginning of dramatic transformation,” says Olly Bartlett, a remote-sensing specialist at the University of Hertfordshire in Hatfield, UK, and an author of the study1, published today in Nature Geoscience, that reports these results.

From white to green

Bartlett and his colleagues analysed images taken between 1986 and 2021 of the Antarctic Peninsula — a part of the continent that juts north towards the tip of South America. The pictures were taken by the Landsat satellites operated by NASA and the US Geological Survey in March, which is the end of the growing season for vegetation in the Antarctic.

To assess how much of the land was covered with vegetation, the researchers took advantage of the properties of growing plants: healthy plants absorb a lot of red light and reflect a lot of near-infrared light. Scientists can use satellite measurements of light at these wavelengths to determine whether a piece of land is covered by thriving plants.

The team found that the area of the peninsula swathed in plants grew from less than one square kilometre in 1986 to nearly 12 square kilometres in 2021 (see ‘An icy land goes green’). The rate of expansion was roughly 33% higher between 2016 and 2021 compared with the four-decade study period as a whole.

“These numbers shocked us,” says Thomas Roland, a study co-author and an environmental scientist at the University of Exeter, UK. “It’s simply that rate of change in an extremely isolated, extremely vulnerable area that causes the alarm.”

The research is “really important”, says Jasmine Lee, a conservation scientist at the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge, UK. Other studies2,3 have found evidence that vegetation on the peninsula is changing in response to climate change, “but this is the first study that’s taken a huge-scale approach to look at the entire region”, she says.

Previous visits to the peninsula led the authors to think that most of the vegetation is moss. As mosses spread to previously ice-covered landscapes, they will build up a layer of soil, offering a habitat for other plant life, Roland says. “There’s a huge potential here to see a further increase in the amount of non-native, potentially invasive species,” he says.

Moss covers rocks on Norsel Point, an arm of an island off the Antarctic Peninsula.Credit: Dan Charman

This is a concern because Antarctica’s native flora are adapted to extreme conditions, and they might not be able to compete with an influx of other species, Lee says.

The researchers point to climate change as the driver of the landscape’s shift from white to green. Temperatures on the peninsula have risen by almost 3 °C since 1950, which is a much bigger increase than observed across most parts of the planet. The “phenomenal” rate of expansion of greenery, Roland says, highlights the unprecedented changes that humans are imposing on Earth’s climate.