This Flesh-Eating ‘Terror Bird’ May Have Stood Over 3 Meters Tall

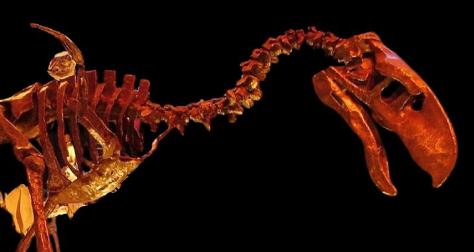

‘Terror bird’ (Titanis walleri) at Florida Museum of Natural History. (Amancer/Flickr/CC BY 2.0)

‘Terror bird’ (Titanis walleri) at Florida Museum of Natural History. (Amancer/Flickr/CC BY 2.0)Though known only from a shinbone fragment, a newly-described flesh-eating terror just might be the largest known member of its feathered kind.

Phorusrhacid ‘terror birds’ stalked what’s now Colombia’s Tatacoa Desert around 12 million years ago, among car-sized armadillo relatives, giant sloths, and saber-toothed marsupial cousins.

The recently analyzed fossil suggests this specimen was far larger than its relatives, which have been estimated to range from 1 to 3 meters (3 and 9 feet) in height.

It also bears signs of how this fearsome predator likely met its end – in the jaws of an even more terrifying beast.

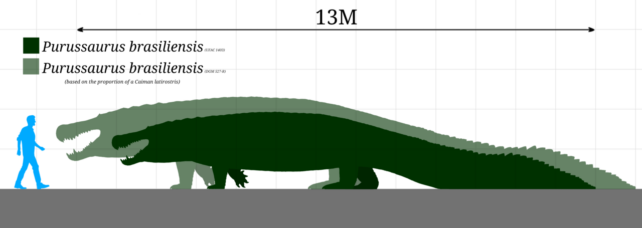

Evolutionary biologist Federico Degrange from Argentina’s Center for Research in Earth Sciences and colleagues found the bird’s shinbone was marred with teeth marks of an ancient crocodile relative, Purussaurus, thought to grow up to 9 meters (30 feet) long.

“We suspect that the terror bird would have died as a result of its injuries given the size of crocodilians 12 million years ago,” says Johns Hopkins University paleontologist Siobhán Cooke.

Past finds reveal Phorusrhacids had massive beaks, making them look awkwardly top-heavy. Those, along with the anatomy of their skull suggests the birds were efficient predators.

“Terror birds lived on the ground, had limbs adapted for running, and mostly ate other animals,” Cooke describes.

Luckily for us, Phorusrhacids were extinct well before humans arrived on the scene.

The bone fragment suggests the animal was up to 30 percent larger than previously known specimens of Phorusrhacids. The team suspects it may be a new species, but its limited remains mean they can’t rule out the possibility that it belongs to previously discovered terror birds like Titanis.

Found laying on the ground by a fossil collector in the Tatacoa Desert, the remains represent the northernmost Phorusrhacid found in South America to date. Back in the Middle Miocene, before South and North America were connected, the area was lush and tropical.

Such conditions typically encourage decay, reducing the chance of fossilization. The scarcity of Phorusrhacid fossils in this region may also suggest these species were apex predators, the researchers explain, which tend to live in much lower densities than their prey.

“The fact that the vast majority of phorusrhacids have been found in southern South America, and that they appear more recently in the Pliocene sediments of southern North America, suggested that terror birds have a South American origin,” Degrange and team write in their paper.

The fossil, first discovered nearly 20 years ago by a curator at the Museo La Tormenta, Cesar Augusto Perdomo, was analyzed using 3D scanning, highlighting the deep pits unique to Phorusrhacid legs.

Today’s closest living relatives to Phorusrhacids are almost an extreme opposite of the giant flightless terrors – they’re instead slight, long-legged, dainty birds, like the red-legged seriema (Cariama cristata).

Giant, flightless birds that are the stuff of nightmares have evolved independently multiple times since non-avian dinosaurs met their end, including Australia’s ‘demon ducks’ and Gastornis of North America and Europe.

This research was published in Papers in Palaeontology.