This isn’t Florkiewicz’s first dive into feline faces. In 2023, she co-led a study revealing that cats can make nearly 300 facial expressions. But how much do they pay attention to the expressions of other cats?

To find out, Florkiewicz—an evolutionary psychologist at Lyon College—decided to investigate something called rapid facial mimicry (RFM). Scientists have known for decades that people and other social mammals such as dogs, horses, and orangutans perform RFM as a crucial part of social bonding. Some even suspect it’s the evolutionary precursor to empathy. “It’s like, if you see someone smiling, you find yourself smiling,” Florkiewicz says.

In the new study, Florkiewicz teamed up with Anna Zamansky, a computer scientist at the University of Haifa. For years, Zamansky’s team has been developing an artificial intelligence (AI) program that recognizes and catalogs the variety of facial expressions cats make.

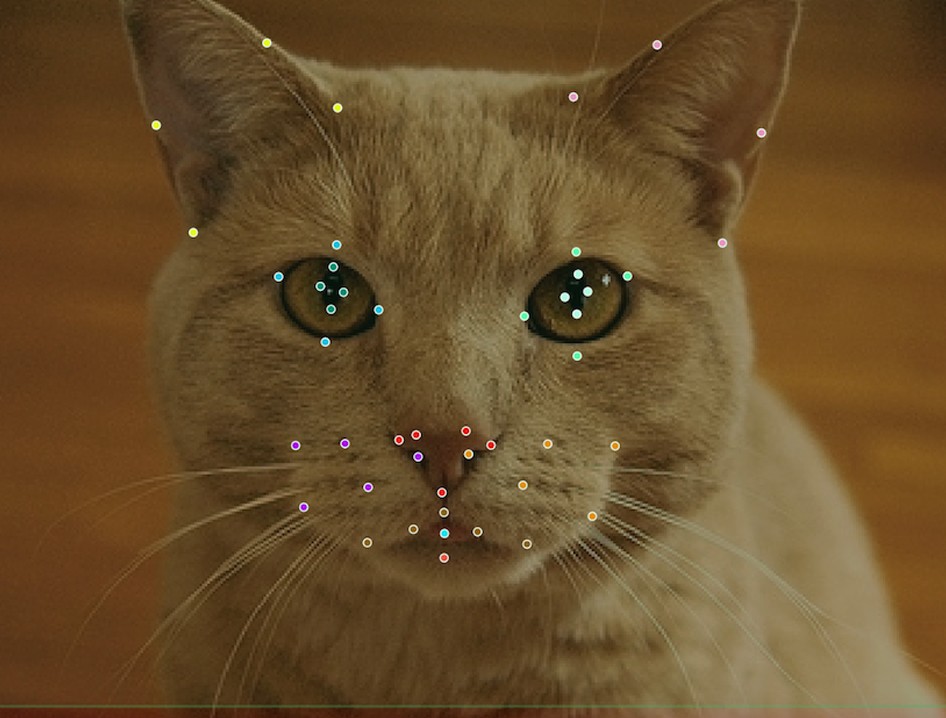

The duo and their colleagues trained the program on hours of videos of cat interactions that Florkiewicz filmed in a Los Angeles cat café as part of her 2023 study. The AI used 48 “landmarks”—digital dots placed virtually on strategic places on cats’ faces—to capture 26 unique facial movements. These, in various combinations, create the hundreds of facial expressions cats make.

Next, the researchers examined how these facial expressions changed when two cats in close proximity looked at each other.

About 22% of the time, the felines mirrored each other, often within a fraction of a second, says co-author Teddy Lazebnik, a computer scientist at Ariel University.

The mirrored expressions were subtle, sometimes just a modest flattening of the ears paired with a small wrinkle of the nose or a tiny raising of the upper lip. But when they happened, the cats began a friendly interaction—playing together, grooming each other, or walking together—almost 60% of the time, he says.

The AI was vital to making the discovery, Zamansky says, as the facial mimicry is “practically impossible to spot via the naked human eye, even among cat experts.”

Yet, such signals are critical for cats—especially because play is “inherently risky” and can “get out of hand,” Florkiewicz says. “Facial mimicry tells them, ‘Is my playmate still having fun? Are we still building a positive social bond?’”

Studies like this may one day help owners choose good feline partners for their cats, or to know when to intervene, Francesconi says. “Using AI to monitor cats’ RFM holds a lot of practical potential,” she says, “especially when it comes to understanding their reactions and needs, preventing conflict, and improving their well-being.”

That might be particularly useful for cheeky cats like Darth Vader. “When I hear Charmander hissing and yowling, I know things might go south pretty quickly,” Florkiewicz says. “I’ll bring Char to my desk for a while, until Vader’s ready to pay attention to her facial expressions well enough to bond once more.”

Darth Vader the cat isn’t quite as evil as his Star Wars namesake. When his shy tabby sister Charmander enters the room, the chubby black feline rotates his ears forward and opens his mouth just a tad. Then he watches for Charmander to do the same. If she complies, the two begin to chase each other around the house in a spirited play session, before finally snuggling up for a bonding nap.