A breathing lung-on-a-chip model developed by the Francis Crick Institute and AlveoliX uses cells from a single donor and mimics the movement of human lungs. The model replicates the early stages of tuberculosis infection and could be used to study influenza, COVID-19 and lung cancer, according to a study published in the journal Science Advances.

|

Scientists build first breathing ‘lung-on-chip’ model using only one person’s cells

The lung model uses induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to create a genetically identical miniature ecosystem.

For the first time, a breathing lung model has been made using cells from only one person.

Announced on January 1, the development comes from researchers at the Francis Crick Institute in London and the Swiss company AlveoliX.

Notably, this “lung-on-chip” model will provide insights into Tuberculosis (TB) and perfect personalized medicine.

The chip acts like lung tissue. Because these chips can actually move like a breathing lung, researchers can use them to see how a specific person’s body fights TB, making it easier to find the right treatment for that individual.

Genetically identical cells

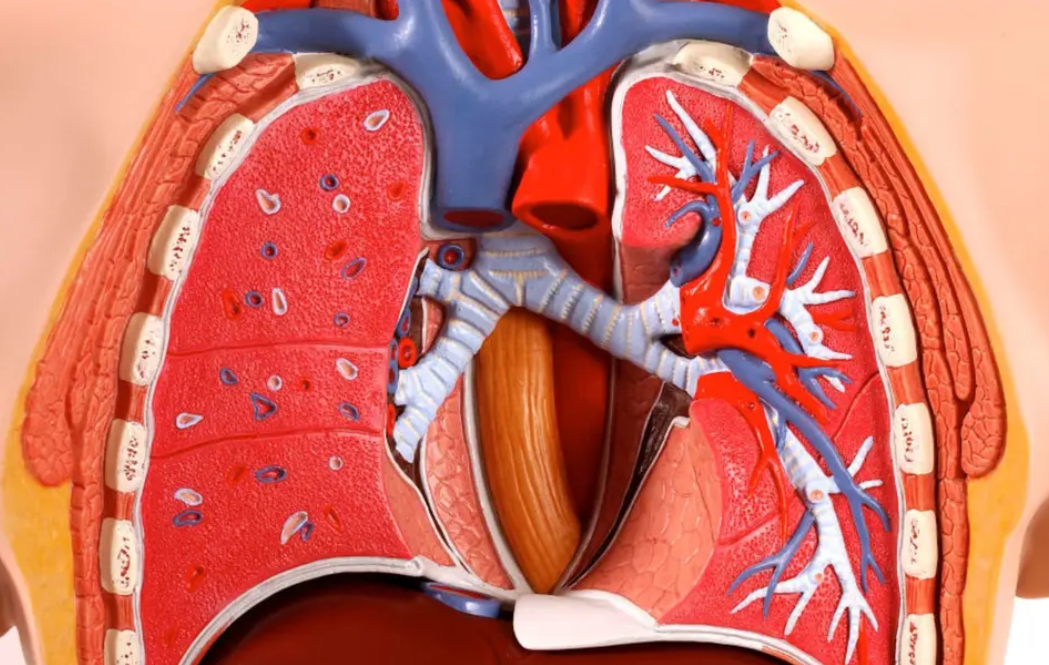

To better understand how the body fights respiratory diseases like flu and TB, scientists are developing “lung-on-chip” technology — miniature, plastic-housed units that replicate the air sacs (alveoli). This is where gas exchange occurs, and infections take hold.

Typically, these models were hampered by using a “mismatch” of cells from different sources, which failed to mirror a single person’s biology accurately.

By finally creating these chips using a single individual’s genetic profile, researchers can now precisely observe the unique battle between human cells and bacteria, something previously impossible.

This breakthrough uses induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to create a genetically identical miniature ecosystem.

“Composed of entirely genetically identical cells, the chips could be built from stem cells from people with particular genetic mutations. This would allow us to understand how infections like TB will impact an individual and test the effectiveness of treatments like antibiotics,” added Gutierrez.

To simulate life, the AlveoliX system uses rhythmic three-dimensional stretching. It pulls and pushes the tissue to mimic the expansion of a human breath.

This mechanical stress is vital. Without it, the cells don’t develop the tiny structures, known as microvilli, that are essential for lung function.

To simulate the infection, researchers populated the chip with donor-matched immune cells (macrophages) and introduced TB bacteria. This allowed them to witness the disease’s first moves within a single, consistent genetic environment.

TB disease replication

TB is a patient’s nightmare because of its stealth. It moves slowly. Months can pass between the first breath of bacteria and the first cough.

By adding the donor’s own immune cells (macrophages) to the chip, the team watched the war unfold in real time.

They witnessed “necrotic cores” — clusters of dead immune cells — forming five days before the entire lung barrier collapsed.

“TB is a slow-moving disease, with months between infection and the development of symptoms, so there’s an increasing need to understand what’s happening in the unseen early stages,” said Jakson Luk, Postdoctoral Fellow in the Host-Pathogen Interactions in Tuberculosis Laboratory and first author.

This technology offers a way out of the ethical and anatomical limitations of animal testing. Mice don’t breathe as humans do, and their immune systems don’t respond to TB the same way ours do.

While the current model focuses on TB, the team is already looking ahead. Flu, COVID-19, and even lung cancer could be the next targets for this tiny, breathing revolution.

The study was published in the journal Science Advances.