Our Ancestors May Have Walked Upright Long Before Leaving The Trees

Humans20 August 2025

(Wirestock/iStock/Getty Images)

(Wirestock/iStock/Getty Images)Early human ancestors may have learned to walk upright on two legs up in the trees rather than on the firm ground of Africa’s ancient savannah.

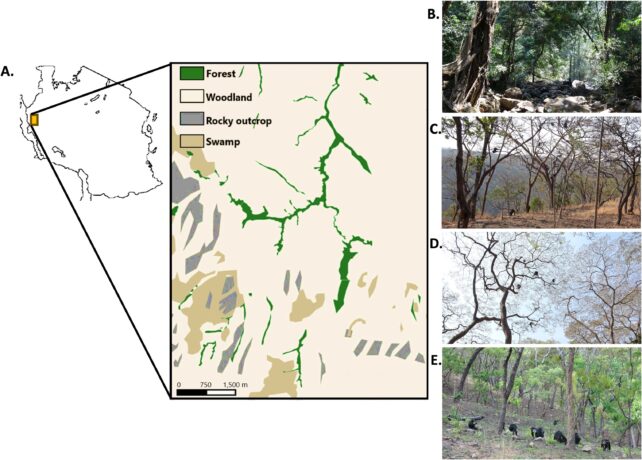

A first-of-its-type study led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany has identified a link between the foraging strategies of Tanzania’s Issa Valley chimpanzees among woodlands and the ape’s locomotion, raising the possibility that our own bipedalism may have helped us reach up, rather than out.

The proposal challenges the clearly ingrained imagery of human ancestors’ tentative first steps: as the climate changed and the landscape opened before them, they were forced to descend from the trees and hoof it across the savannah, braving big cats and an alien environment to find food and shelter.

“For decades it was assumed that bipedalism arose because we came down from the trees and needed to walk across an open savannah,” says Max Planck Institute anthropologist Rhianna Drummond-Clarke

So, when did early human ancestors start walking, and why?

These are two of the most tantalizing questions in paleoanthropology. By studying chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) tree-foraging behaviors in relation to tree types, researchers behind this most recent investigation have uncovered a few clues.

Issa Valley chimpanzees live in savannah-mosaics, which are dry, open woodlands similar to the paleohabitats traversed by early hominins, a ‘tribe’ including current humans and extinct ancestors. These are among the driest chimpanzee-inhabited areas in the world, where grass fires burn more than 75 percent of the landscape during the May-October dry season.

Surprisingly, the Issa Valley chimpanzees in savannah-mosaics spent an unexpected amount of time up in the trees – just as much as the chimpanzees that live in densely vegetated forests. This is partially due to their food sources requiring more ‘processing,’ as seeds must first be removed from seed pods, and unripe fruits are more fibrous and take more effort to eat.

Yet here’s the intriguing part: since chimpanzees are relatively large, they move through the trees by suspending themselves from branches, or standing and walking upright while holding onto nearby branches for balance.

The unexpected level of arboreality and branch-walking displayed by these chimpanzees, which have been noted before in other populations, lends support to hypotheses that suggest ancient apes and human ancestors may have gradually shifted toward habitual bipedalism, or walking upright, in an arboreal environment.

The idea contrasts the popular assumption of why we took so readily to walking on two legs.

Toward the closing of the Miocene Epoch (23 to 5.3 million years ago), forests turned into savannahs and ostensibly pushed hominins into orthograde locomotion (upright walking) to better navigate an open landscape with more sparsely spaced food sources.

Unfortunately there’s a lack of hominid fossils dating around the end of the Miocene and beginning of the Pliocene circa 4 to 7 million years ago; a key period that may have seen a more widespread emergence of habitual bipedalism in response to this ecological change.

If anything, fossil evidence from the late Miocene shows that several extinct hominins still had tree-dwelling features, including relatively elongated upper limbs and curved fingers.

Furthermore, studies of dental wear and carbon isotopes suggest that some hominins still significantly relied on food sources from trees even when living in open habitats. Some of their diets may have been similar to those of extant chimpanzees, making them an invaluable analog for comparison.

“We suggest our bipedal gait continued to evolve in the trees even after the shift to an open habitat,” explains Drummond-Clarke.

Like using training wheels on a bicycle, human ancestors may have practiced their gait up in trees where they could grasp branches for balance. As a result, they gradually built the upright movement skills needed to survive in newly open habitats with scarcer food sources and, eventually, spread to almost every corner of the globe.

This research is published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.